Did a bard to the Scots throne see visions of the future?

Did a bard to the Scots throne see visions of the future?

Thomas the Rhymer, True Thomas, Thomas of Ercildoune, Lord Learmonth; he goes under various names. He is remembered for his prophecies of the borders and other Scottish events, and an anonymous ballad about him was retold by Sir Walter Scott in Minstrelsy of the Scottish Borders, and a rendition of this was released in song by Steeleye Span in 1974. He has appeared many times in folk tales, books and more recently in graphic novels. But one thing we can be sure of; he was a real historical character.

He was a wise and learned man living in 13th century Scotland, bard to and lifelong friend of Alexander III (King of Scots 1249-1286). In The Romance and Prophecies of Thomas of Ercildoune (Edited by AJH Murray) we learn that the name Thomas Rymour de Ercildoune occurs on a deed whereby Petrus de Haga de Bemersyde agrees to pay half of stone of wax annually to the Abbot of the Convent of Melrose. Another bill, dated 1294, has Thomme Rymour de Ercildoune, son of Thomas the Rhymer, granting all the family lands in Ercildoune (modern day Earlston) to the Trinity House of Soltra (Soutra). We therefore see that Thomas was a man of substance. Certainly, he is said to have stayed in a tower house to the west of Earlston, the remnants of which stand unto this day. Yet it is not for his wealth or influence that he is remembered but rather for his prophecies and the legend surrounding him.

He was a wise and learned man living in 13th century Scotland, bard to and lifelong friend of Alexander III (King of Scots 1249-1286). In The Romance and Prophecies of Thomas of Ercildoune (Edited by AJH Murray) we learn that the name Thomas Rymour de Ercildoune occurs on a deed whereby Petrus de Haga de Bemersyde agrees to pay half of stone of wax annually to the Abbot of the Convent of Melrose. Another bill, dated 1294, has Thomme Rymour de Ercildoune, son of Thomas the Rhymer, granting all the family lands in Ercildoune (modern day Earlston) to the Trinity House of Soltra (Soutra). We therefore see that Thomas was a man of substance. Certainly, he is said to have stayed in a tower house to the west of Earlston, the remnants of which stand unto this day. Yet it is not for his wealth or influence that he is remembered but rather for his prophecies and the legend surrounding him.

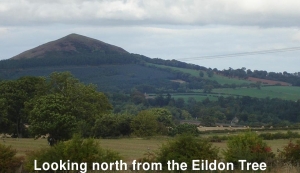

Thomas was a harpist and the legend of how he came by his prophetic gift has him playing his harp at the Eildon Tree, a beauty spot on Huntlie Bank, at the foot of the Eildon Hills near Melrose. It is here that the Fairy Queen appears to Thomas and in the wonderful style of Scots ballads, seduces him. Thomas having made love to the Elfin Queen, she spirits him away to Elfland for what he believes to be three days and three nights but which turns out to be seven years. Upon his return to Earth, the Fairy Queen gives Thomas a magic apple, eating which gives him the “Tongue whit canna lee” or the gift of prophecy in rhyme.

Thomas was a harpist and the legend of how he came by his prophetic gift has him playing his harp at the Eildon Tree, a beauty spot on Huntlie Bank, at the foot of the Eildon Hills near Melrose. It is here that the Fairy Queen appears to Thomas and in the wonderful style of Scots ballads, seduces him. Thomas having made love to the Elfin Queen, she spirits him away to Elfland for what he believes to be three days and three nights but which turns out to be seven years. Upon his return to Earth, the Fairy Queen gives Thomas a magic apple, eating which gives him the “Tongue whit canna lee” or the gift of prophecy in rhyme.

So Thomas returned to Earth at the Eildon Tree, which itself features in one of his prophecies, which today is carved in the ground at the site of the Eildon Tree;

At Eildon Tre, if ye sall be,

A brigg ower Twede ye there micht se.

The only bridge across the River Tweed in the days of Thomas the Rhymer was a small affair built to carry the Roman road Dere Street across the river. Whilst it would be likely, if not inevitable, that another bridge would be built in the Earlston/Melrose area, in the 13th Century it would nonetheless have seemed as nonsense that any bridge could be seen. It is impossible to see the Tweed from the site of the Eildon Tree due to the topography of the land and it is more than likely that the bare fields around nowadays would have been heavily afforested in the days of Thomas.

The only bridge across the River Tweed in the days of Thomas the Rhymer was a small affair built to carry the Roman road Dere Street across the river. Whilst it would be likely, if not inevitable, that another bridge would be built in the Earlston/Melrose area, in the 13th Century it would nonetheless have seemed as nonsense that any bridge could be seen. It is impossible to see the Tweed from the site of the Eildon Tree due to the topography of the land and it is more than likely that the bare fields around nowadays would have been heavily afforested in the days of Thomas.  In 1864 however the Berwickshire Railway was built from Duns via Earlston to Ravenswood, near St Boswells. Part of this undertaking was the erection of the magnificent Leaderfoot Viaduct and the top of this beautiful listed structure can just be seen from the site of the Eildon Tree to this day.

In 1864 however the Berwickshire Railway was built from Duns via Earlston to Ravenswood, near St Boswells. Part of this undertaking was the erection of the magnificent Leaderfoot Viaduct and the top of this beautiful listed structure can just be seen from the site of the Eildon Tree to this day.

Other prophecies focused around the areas known to Thomas and the most famous of these surrounds the Haig family of Bemersyde House;

Betide, betide, white’er betide,

Haig sall be Haig o’ Bemersyde.

There were no doubt those who have said that this was just Thomas trying to ingratiate himself with a local lord and the line of Haig of Bemersyde became extinct in the 19th century, which would seem to have put paid to the prophecy. Following the First World War however, a grateful UK government granted Bemersyde House to Field Marshall Earl Haig, who was of a minor line of Haig of Bemersyde and his descendents in perpetuity. Today and for the foreseeable future therefore, Haig shall be Haig of Bemersyde. Vistors to Bemersyde today are only allowed to visit the gardens. I was fortunate enough however to meet the present Earl Haig whilst there and when I told him I was researching Thomas, he allowed me to see the lintel of the ancient peel tower, which bears his crest and family motto “Whatever Betide”.

There were no doubt those who have said that this was just Thomas trying to ingratiate himself with a local lord and the line of Haig of Bemersyde became extinct in the 19th century, which would seem to have put paid to the prophecy. Following the First World War however, a grateful UK government granted Bemersyde House to Field Marshall Earl Haig, who was of a minor line of Haig of Bemersyde and his descendents in perpetuity. Today and for the foreseeable future therefore, Haig shall be Haig of Bemersyde. Vistors to Bemersyde today are only allowed to visit the gardens. I was fortunate enough however to meet the present Earl Haig whilst there and when I told him I was researching Thomas, he allowed me to see the lintel of the ancient peel tower, which bears his crest and family motto “Whatever Betide”.

Thomas was a learned man whom apart from his prophecies was believed to be a great storyteller and, surprising as it may seem, he was the first to pen the story of Tristan and Isolde. It may well have been this and his harp playing which led him to become Bard to and closest confidant of King Alexander III, a friendship which ended with the king’s accidental death, which Thomas foretold.

Thomas was a learned man whom apart from his prophecies was believed to be a great storyteller and, surprising as it may seem, he was the first to pen the story of Tristan and Isolde. It may well have been this and his harp playing which led him to become Bard to and closest confidant of King Alexander III, a friendship which ended with the king’s accidental death, which Thomas foretold.

There are three versions of this. The first has Thomas staying with Earl Douglas at Dunbar and being taunted to give a prophecy. The second has Thomas seeing the apparition at the wedding of Alexander III and his second wife, Yolande de Druex. The third version, which is the one I am most familiar with, takes place at a masque ball in Edinburgh Castle on the night of 19th March 1286.

At the ball, everyone is making merry, apart from Thomas, whom Alexander III observes is somewhat agitated and keeps scanning the dance floor from his place beside the king. He asks Thomas what is troubling him, to which the old seer replies that there is one at the ball who was not invited. When asked whom, Thomas replies the man in the red cloak. The king and his lords see no such person and chide Thomas, suggesting he has had too much wine. Thomas is adamant that that he could see the uninvited guest and takes it as an ill omen.

Whichever of the three versions, they all tell that Thomas then uttered this prophecy;

Alas for the morrow, a day of calamity and misery. Before the twelfth hours shall be heard such a blast so vehement that it shall exceed all those that have been heard in all Scotland. A blast which will strike the nations with amazement, shall confound those who hear it, shall humble what is lofty and what is unbending shall level to the ground.

Returning to the legend, Thomas begs the king not to ride out that night as he had planned. But Alexander, fired with wine and anxious to be with his young bride at Kinghorn Castle in Fife, was having none of it. After a treacherous crossing of the Firth of Forth at the Queen’s Ferry (modern day Queensferry), Alexander headed east along the Fife coast. He had almost reached Kinghorn but had lost his stewards in the storm. Undeterred, he pushed his steed onward – and right over the cliffs above Pettycur Bay to his death. Some six hundred years later, the above legend became known to a young American author named Edgar Allen Poe, who used it as his inspiration for his Gothic horror novel The Masque of the Red Death.

Returning to the legend, Thomas begs the king not to ride out that night as he had planned. But Alexander, fired with wine and anxious to be with his young bride at Kinghorn Castle in Fife, was having none of it. After a treacherous crossing of the Firth of Forth at the Queen’s Ferry (modern day Queensferry), Alexander headed east along the Fife coast. He had almost reached Kinghorn but had lost his stewards in the storm. Undeterred, he pushed his steed onward – and right over the cliffs above Pettycur Bay to his death. Some six hundred years later, the above legend became known to a young American author named Edgar Allen Poe, who used it as his inspiration for his Gothic horror novel The Masque of the Red Death.

Thomas of course, may have just been using common sense by telling the King “You’re surely not going out in that?” Even today, if our present Queen, wanted to go riding a horse along the Fife coast on a filthy night while drunk, I’m sure that even the most diehard republican would strongly advise her against it.

In the 19th century a memorial was erected on the Burntisland to Kinghorn Road to the memory of Alexander III. On the wall next to this there is a plaque with a cantus from the oldest known piece of Scots poetry, which is also attributed to Thomas the Rhymer;

Quhen Alysander oor King wes deid,

That Scotland led in luf and le,

Awey wes sons o’ ale and breid,

O’ wyne and wax, o’ gamyn and gle.

Oor gowd wes changit intae leid,

The fruite falyett aff everilk tre,

Cryst! Borne intae Vyrgynitie,

Succour Scotland and remedie,

That stade is in perplexitie.

(When Alexander our King was dead,

That Scotland led in love and law,

Gone were days of ale and bread,

Of wine and candles, of gambling and glee.

Our gold was changed all into lead,

The fruit fell from every tree.

Christ! Born of virginity,

Succour Scotland and remedy,

That state is in perplexity.)

A state in perplexity indeed. The consequences of the untimely death of the last Celtic King of Scots were to be disastrous for Scotland. Alexander had outlived his son by two years. His daughter, Margaret, had been married to King Eirik II of Norway and had died in 1283, while giving birth to a daughter, also named Margaret and known as the Maid of Norway. So the Scots crown now rested on the three year old granddaughter of the late King in far-off Norway. Worse was to come. A sickly child herself, little Queen Margaret died aged 7, on her way to Scotland in 1290. Civil war erupted in Scotland as no fewer than 13 men (known as The Devil’s Dozen) rose up to claim the Scots crown. In an attempt to quell the dispute the Bishops of Scotland (then the real power behind the throne) thought it would be a good idea to ask nice King Edward I of England to adjudicate over the matter. Instead he declared himself Overlord of Scotland and placed the puppet-king John Balliol on the throne in 1292, before deposing him four years later. This eventually led to the Wars of Independence which were to drag on from 1296 until 1328.

It seems however that Thomas was aware of what was to come from one of his shortest, yet most accurate prophecies;

The Burn o’ Breid,

Sall rin fu’ reid.

(The river of bread, Shall run full red.)

And where in Scotland do we find a “river of bread”? The Bannock Burn of course, which did indeed run fully red on 24th June 1314 when the English army at the foot of a hill on marshy ground before them and the Bannock Burn behind them were decimated when the Scots charged downhill from the New Park above Stirling. A great number of English were forced into the river, where they either drowned, pulled down by their chainmail, or died of their wounds. It was recorded that for weeks after the battle it was possible to cross the Bannock Burn on the bodies of the English without getting ones feet wet.

And where in Scotland do we find a “river of bread”? The Bannock Burn of course, which did indeed run fully red on 24th June 1314 when the English army at the foot of a hill on marshy ground before them and the Bannock Burn behind them were decimated when the Scots charged downhill from the New Park above Stirling. A great number of English were forced into the river, where they either drowned, pulled down by their chainmail, or died of their wounds. It was recorded that for weeks after the battle it was possible to cross the Bannock Burn on the bodies of the English without getting ones feet wet.

At least one commentator has recorded this in a more fanciful way;

Of Bruce’s side a son shall come, From Carrick’s Bower to Scotland Throne. A Red Lion bearth he. The foe shall tread the lion down, A score of years but three; Till Red of English blood shall run, Burn of Bannock to the sea.

Whilst it would be nice to believe in this prophecy, it appears by language alone to be a modern, perhaps 19th century, romanticism. And it is chronologically incorrect as well. “A score of years but three” gives seventeen years, which when added to 1306, the year of Bruce’s coronation, gives 1324, not 1314, the year of the Battle of Bannockburn. Even if we take it as 1296, the year the Wars of Independence commenced, that still only gives us 1313, a year short of the target. The rhyme is possibly a reworking mainly of lines from the first publishing of Thomas’s prophecies in The Whole Prophecie of Scotland which was published in 1603;

A French wife shall bear the son, Shall rule all Britaine to the sey, That of the Bruces blood shall come, As neere in nint degree. I famed fast what was his name, Where that he came from what countrie. In Erstlingtoun, I dwell at hame, Thomas Rymour men calls me.

Nonsense of course, for neither Bruce nor any of his descendents ever ruled the whole of Britain. It is worth noting that Bruce is indeed named in this version of the prophecies. He is also named in The Romance and Prophecies;

The Bretons blode shall vnder fall, The Brucys blode shall wyn the spraye.

Another prophecy tells of a battle “…between Seytoun and the sea…” and the same part of The Romance and Prophecies mentions “Gladysmore”, modern day Gladsmuir in East Lothian. Due to this the battle has been interpreted as either the Battle of Pinkie of 1549 or the Battle of Prestonpans of 1746, amongst others. What commentators seem to have missed however is the importance of the name “Seytoun”. Many would think this to refer either to Port Seton or Seton Collegiate Church in East Lothian. Yet the origin of these place names lie with Fa’side Castle, to the west of Tranent. After the Battle of Bannockburn, Fa’side was given by Robert the Bruce to his nephew, Sir Alexander Seton, for spying on the English. Therefore, the very naming of “Seytoun” in relation to East Lothian is in itself a fulfilled prophecy.

Away from matters of war, one of Thomas’s prophecies predicted another Royal succession, that of the Union of the Crowns;

When Twede and Pausail meet at Merlin’s Grave,

Scotland and England sall ane King have.

The Merlin Stone on Drumelzier Haugh, between Biggar and Peebles, is the alleged burial place of Merlin. The Powsail was the burn which ran through the Drumelzier village, now the Drumelzier Burn, which does indeed flow into the River Tweed. It is claimed that on the night of 24th March 1603, the Powsail and the Tweed flooded as far up as the Merlin Stone. It is a matter of historical fact that on the same evening Elizabeth Tudor, Queen of England, passed away without issue and the throne of England fell to James VI, King of Scots, who thereafter fashioned himself as “King of Great Britain”. Detractors may point out that the year 1603 also saw the first publishing of Thomas’s Prophecies in The Whole Prophecie of Scotland. However, if the publishers were trying to ingratiate themselves to the king, then it would have fallen upon deaf ears and they were even risking their lives by publishing the prophecy. James VI was a highly puritanical man who had over 500 people, mainly women, burnt at the stake for witchcraft during his reign, and who had Drumelzier Castle, near the Merlin Stone, razed to the ground. He opposed anything remotely connected with the occult and anyone trying to curry favour with him through a prophecy would be more likely to incur his wrath. I would therefore venture that the above prophecy were indeed the words of Thomas the Rhymer.

The Merlin Stone on Drumelzier Haugh, between Biggar and Peebles, is the alleged burial place of Merlin. The Powsail was the burn which ran through the Drumelzier village, now the Drumelzier Burn, which does indeed flow into the River Tweed. It is claimed that on the night of 24th March 1603, the Powsail and the Tweed flooded as far up as the Merlin Stone. It is a matter of historical fact that on the same evening Elizabeth Tudor, Queen of England, passed away without issue and the throne of England fell to James VI, King of Scots, who thereafter fashioned himself as “King of Great Britain”. Detractors may point out that the year 1603 also saw the first publishing of Thomas’s Prophecies in The Whole Prophecie of Scotland. However, if the publishers were trying to ingratiate themselves to the king, then it would have fallen upon deaf ears and they were even risking their lives by publishing the prophecy. James VI was a highly puritanical man who had over 500 people, mainly women, burnt at the stake for witchcraft during his reign, and who had Drumelzier Castle, near the Merlin Stone, razed to the ground. He opposed anything remotely connected with the occult and anyone trying to curry favour with him through a prophecy would be more likely to incur his wrath. I would therefore venture that the above prophecy were indeed the words of Thomas the Rhymer.

Some of Thomas’s prophecies concern locations in the Highlands, which I personally find surprising. Lowland Scots travelling in the Highlands is a relatively new phenomenon, really only taking off after the Highlands were romanticised by the novels of Sir Walter Scott. Before then Lowlanders tended to avoid the Highlands, considering them to be a desolate and unforgiving place, full of wild animals (wolves and bears still roamed the Highlands in the days of Thomas) and barbaric, untrustworthy people. I also discovered during my research that some commentators attempt to attribute Thomas with prophecies relating to the Battle of Culloden of 1746 and the Highland Clearances. They are obviously confusing Thomas with another prophet, Kenneth Odhar, The Brahan Seer, who correctly prophesied these events.

Nevertheless Highland prophecies attributed to Thomas do exist. One concerns the forfeiture of Inverugie, also known as Dunnottar Castle, which is perched on a rocky outcrop in the North Sea, to the south of Stonehaven;

Nevertheless Highland prophecies attributed to Thomas do exist. One concerns the forfeiture of Inverugie, also known as Dunnottar Castle, which is perched on a rocky outcrop in the North Sea, to the south of Stonehaven;

Inverugie (Dunnottar) by the sea,

Lordless sall thy landis be:

And underneath the hearth stane,

The tod (fox) sall bring her birdis (young) hame.

Dunnottar, which was once fully self-sufficient and at one point even had its own brewery, was seized by the Crown from the Earl Marischall of Scotland for his part in the Jacobite Rebellion of 1715. It is today uninhabited. The stone from where Thomas was said to have made his prophecy was removed to build a church in 1763 but the field in which it stood is still named “Tamma’s Stane”.

Another Highland prophecy takes the form of a curse. The story goes that the Earl of Fyvie, not wanting to offend Thomas should he visit left the castle gates open for seven years and a day. On the evening that Thomas did arrive, however, there was a storm and the gates blew shut in his face. Thomas is said to have uttered;

Another Highland prophecy takes the form of a curse. The story goes that the Earl of Fyvie, not wanting to offend Thomas should he visit left the castle gates open for seven years and a day. On the evening that Thomas did arrive, however, there was a storm and the gates blew shut in his face. Thomas is said to have uttered;

Fyvie, Fyvie, thou a’ never thrive,

As lang’s there’s in thee stanis (stones) thrie:

There’s ane intill the highest tower,

There’s ane intill the Ladye’s bower,

There’s and aneath the water-yett (gate),

And thir thrie stanis ye a’ ne’er get.

Since 1433 no heir of Fyvie has been born within the castle walls and it has never passed from father to eldest son. No first-born among the last owners, the Forbes-Leith family, inherited Fyvie and it has been in the hands of the National Trust for Scotland since 1984. Only the stone in the Ladies Bower has ever been found and it is kept in the Charter Room of the Castle. It is a mysterious object in itself, as at times it is bone dry but at others has been witnessed to exude enough water to fill the bowl.

One prophecy from the north-east of Scotland would appear at first to be a nonsense poem:

When Dee and Don sall rin in one,

When Dee and Don sall rin in one,

And Twede sall rin in Tay,

The bonny water o’ Urie,

Sall bear the Bass awey.

The Dee and the Don are the two rivers which flow through Aberdeen into the North Sea and obviously cannot run as one and Tweed and Tay, being over 100 miles apart cannot run into each other. The Bass of Inverurie is formed of two 50 foot high mounds which formed part of the old motte and bailey castle built by the Garioch family in the 1100s. Having visited the Bass I would say they are highly unlikely to ever be washed away and I believe that this is what Thomas was saying in this otherwise nonsensical quatrain.

So what became of Thomas the Rhymer? As we have seen, his son made over the family lands to the Holy Trinity of Soltra in 1294, thereby suggesting that he was dead by that time. An inscription on the east wall of Earlston Kirk would seem to suggest that he died in his hometown. It reads;

Auld Rymer’s race,

Lyes in this place.

Note however that it reads “Auld Rymer’s race”, which may suggest that it is in fact a family tomb and not necessarily the grave of Thomas the Rhymer himself. His son after all was named in the 1294 document as Thomme Rymour de Ercildoune. It is possible that either Thomas of his descendants took “Rymour” as a family name, in much the same fashion as the way the Fitzallan family, who were hereditary High Stewards of Scotland took the name “Stewart”. Notice also the use of the plural “Lyes”.

Note however that it reads “Auld Rymer’s race”, which may suggest that it is in fact a family tomb and not necessarily the grave of Thomas the Rhymer himself. His son after all was named in the 1294 document as Thomme Rymour de Ercildoune. It is possible that either Thomas of his descendants took “Rymour” as a family name, in much the same fashion as the way the Fitzallan family, who were hereditary High Stewards of Scotland took the name “Stewart”. Notice also the use of the plural “Lyes”.

Yet Thomas may not have died in Earlston in or before 1294. A poem by Blinde Harry, Minstrel to the Court of James IV (King of Scots, 1488-1513) tells of Thomas living in The Faile, a Cluniac monastery in Ayr. The poem claims that Thomas witnessed the body of William Wallace being thrown over the castle walls by English soldiers, believing him to be dead, only to be nursed back to health. I have come across this legend elsewhere, which would seem to attest to the validity of the story. And if Thomas did witness it, then he must have still been alive around 1295, the year of Wallace’s uprising, or thereafter. He may well have retired to the Faile after instructing his son to donate the family lands to the Holy Trinity of Soltra. Nobody knows the year of his birth but given he was by the side of Alexander III from his boyhood until his untimely death, Thomas must have been of an extremely good age by then.

Or did he, as the legend has it, rise up one evening, put on his mantle of green given him by the Elfin Queen, pick up his harp and follow a white hart and a white doe into the middle of the Eildon Hills, never to be seen again? We shall simply never know.

And what of the prophecies themselves, if they are indeed his? The tradition was oral until the first publication in 1603 and therefore there is every chance that rhymes may have been added (or omitted) for propaganda purposes. There are also of course prophecies which did indeed fail, or not come about as expected. There is a legend that when Alexander III was due to marry Yolande de Druex in 1285, Thomas warned the King not to marry in Kelso Abbey as the roof would fall in. The ceremony was moved to Jedburgh Abbey and the roof of Kelso Abbey did indeed fall in. Okay, the latter happened 500 years later but it still happened.

But failures, additions and omissions do not account for certain facts about the prophecies of Thomas the Rhymer. The forfeiture of Dunnottar of 1715, the building of Leaderfoot Viaduct in 1864 and the granting of Bemersyde House to Earl Haig and his successors in 1921 are but only some of the prophecies which appear in the 1603 publication but which have since come to pass. For that there is no logical explanation and other prophecies may yet come to pass in the future.

Sceptic, believer or indifferent, it is for each of us to make up our minds. The Law of Causality states that there are an infinite number of possible futures continually happening from moment ot moment, which would seem to preclude any attempts at prophecy. Yet if there are those with the ability to foresee things which are yet to be, then it is surely as much a curse as it is a blessing. At face value it certainly appears that Thomas Learmonth of Ercildoune was indeed one of these people, and as such I can do no fairer than leave the last word to the man himself;

Sceptic, believer or indifferent, it is for each of us to make up our minds. The Law of Causality states that there are an infinite number of possible futures continually happening from moment ot moment, which would seem to preclude any attempts at prophecy. Yet if there are those with the ability to foresee things which are yet to be, then it is surely as much a curse as it is a blessing. At face value it certainly appears that Thomas Learmonth of Ercildoune was indeed one of these people, and as such I can do no fairer than leave the last word to the man himself;

Whan the saut gangs abune the meal,

Believe nae mair o’ Tammie’s tale.

(When salt cost more than meat, believe no more of Thomas’s prophecies)

The original of this article was a talk given by the author, Leslie Thomson, to the Edinburgh Fortean Society on 13 August 2003.